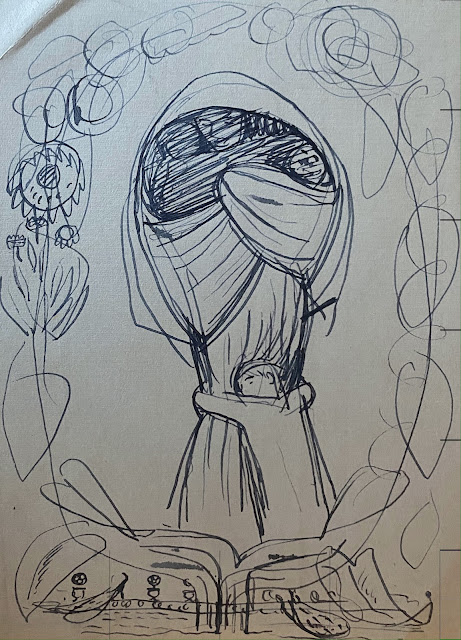

'Maternity bud' 1937 Pen and ink on cartridge paper Photograph ©LissLlewellyn

In about 1936 Evelyn started, from not much more than a doodle, to design a personal letter format, consisting of a vase, flower pot or stylised flower bed, from which grew two flowered stems up the sides of the paper, between which she wrote her message.

Designs for personal correspondence, c.1936. Image ©LissLlewellyn

The letter reproduced above is one of the very few in this format that survive. Mostly they are uncoloured, but Evelyn has pulled the stops out to congratulate her first-year Royal College of Art tutor, Allan Gwynne Jones, who became a lifelong friend, on his engagement to Rosemary Allan, a fellow artist. She calls him 'Sir', not because he has been knighted (he never was) but out of a friendly respect.

As often the case with Evelyn, there may be some decoding to do: is there any significance in tulips, carnations and harebells growing out of a three-year old rose stock? Did Allan Gwynne Jones have a walled garden with one door open, the other closed? One can only wonder, and maybe wonder at the purpose of such an exercise, but clearly it suited her fancy to vary the flowers and the setting to complement the character of her correspondent or the subject of her message.

By late 1936 or early 1937 it appeared to Evelyn that her relationship with Charles Mahoney, a former Royal College of Art tutor and later lover, was coming apart. She had shared with him their major work to date, the extensive murals at Brockley School in south-east London, which were inaugurated in February 1936. The later mural panels hinted at the autumn of their relationship. Nevertheless Evelyn saw her future in partnership with Mahoney, professional as well as personal.

Evelyn's letters to Mahoney suggest that he needed some encouragement to take part in their only professional joint venture, Gardeners' Choice, published by Routledge in late 1937 and reprinted by Persephone Books in 2015. It's arguable how genuine a joint venture this somewhat forward-looking gardening book was. As for their personal relationship, the same series of letters carries Evelyn's frequent suggestions for gardens they might develop together, houses they might live in together, places they might travel to together. Eventually she made her top call: to cement the union they should have children together. She made this clear in a series of images, mostly in drawings in her letters, but occasionally in more weighty formats, like the canvas entitled Opportunity, closely examined here. Below is the most evolved of the Opportunity images. The reference to Mahoney is at once clear: sunflowers, as seen in Opportunity's hat and at the top of the ladder, and in many of his other paintings, might well be said to be Mahoney's trade-mark.

It seems curious that a 30-year-old woman should need, or feel obliged, to communicate with her lover about their personal procreation by coded drawings. (And possibly more bizarre to work up her sketches into oils, later to be exhibited in public and sold, as was the case with Opportunity above, admittedly after Evelyn and Mahoney had separated.) Perhaps procreation was something Evelyn found difficult to talk about. She may have had a distressing liaison in Germany some years earlier. Maybe it really was easier and less traumatic for her to express herself through drawings. There's no evidence that Mahoney ever saw her early sketches, which amplified an ingenious and original idea.

Studies for 'Maternity bud' (1) Pen and ink on writing paper. 1937. Photograph ©LissLlewellyn

In the top left hand corner there are the surround stems, growing out of a fluted bowl and culminating in a crudely-drawn sunflower. Mahoney is being invoked and addressed, through his trade-mark flower. In the centre is a shape perhaps reminiscent - at this stage - of a sheaf of wheat, being held together by a small boy wrapping his arms round it. Various unexplained shapes occupy the bulbous swelling at the top of the sheaf. Moving clockwise, the sheaf gives way in prominence to a roughly drawn peacock, probably another reference to Mahoney and Evelyn's habit of sometimes calling him (with no hint of a ruder vernacular) 'cock' and 'matey cock'.

Further clockwise, the bulge at the top of the sheaf appears to show something quite remarkable: two shadowy human figures, apparently wrapped in a sort of caul. Finally, more detail of the small boy hugging the sheaf. A similar sketch amplifies some of these elements:

Studies for 'Maternity bud' (2) Pen and ink on writing paper. 1937. Photograph ©LissLlewellyn

Moving left to right, the 'sheaf' is now seen to contain, and to shelter and protect in its folds, a mother-figure centrally with - it isn't very clear - a tiny baby on her left and a slightly older one on her right. The sheaf-hugging boy is shown in greater detail. The fluted bowl is set in a formal garden, with gateposts, a columned balustrade and two attendant peacocks, like heraldic supporters. The stem of the plants, here reduced to a single line, has somehow retained its thorns.

Finally Evelyn arrives at a version close to the definitive image at the top of this essay:

Sketch for 'Maternity bud' (3) Pen and ink on writing paper. 1937. Photograph ©LissLlewellyn

The same peacocks in their balustraded parkland, the same stem (although without its thorns), the same sunflower insistence, but a little more detail in the human figures contained within the folds of what is now more evidently not a caul, but a sort of prepuce: a mother-figure centrally, babies either side. Perhaps we can now see that the boy gives scale to the phallus he is holding upright and erect. In botany the bud contains the seed: the phallus resembles the stem and the bud. Is she implying that the maternity for which she longed lay at the tip of Mahoney's manhood?

Did Mahoney ever see these drawings? It's possible that he never did. All Evelyn's known letters to Mahoney are preserved in the Tate Archive, the generous gift of his daughter. Although some letters from the final anguished months of their relationship may have been suppressed, none of the known letters contains material anything like that shown here. This material comes exclusively from the Hammer Mill Oast collection, the contents of Evelyn's residual studio, passed on to her siblings at her death in 1960.

Although Mahoney, in a hearsay and unverifiable remark, replied to Evelyn's urgings by saying children would stunt both their careers, nevertheless he presumably responded to some extent, because in the autumn of 1937 Evelyn miscarried. The authority for this was Roger Folley, the RAF officer and - in peace time - horticultural economist, whom she married in 1942, and in whom she confided when, to her mortification, it was discovered that she was unable to conceive.

In the spring of 1936 Evelyn left the Brockley lodgings she had rented while working on the later Brockley murals and returned to The Cedars. She saw Mahoney at weekends. Occasionally they went to stay with friends together, notably with Edward and Charlotte Bawden at Great Bardfield, where because of their dedication to gardening they had been for some time nicknamed 'Adam and Eve'. This was the summer of the Opportunity images. It was also the summer dominated by Gardeners' Choice, planning, writing, choosing plants and travelling to see them, sometimes to Evelyn's aunt, the green-fingered Clara Cowling, whose East Sussex house, Steellands, featured in some of Evelyn's decorative vignettes. To work on the book Mahoney sometimes went to stay near Evelyn in Rochester, not at The Cedars, but at 42 St Margaret's Street, not far from the castle and cathedral. We can perhaps dare to hope that Evelyn was happy in that summer and autumn: she and Mahoney were working together on a joint project and the subject of a closer union through children had at least been broached.

Work continued on the book throughout the spring of 1937. Evelyn sketched Mahoney drawing plants that would feature in Gardeners' Choice. Paul, the Dunbars' dog, seems unimpressed.

*Routledge intend to include Gardeners' Choice in their Christmas 1937 list. Proofs have to be in by September if the book is to appear on booksellers' shelves in good time.

*Edward Bawden is reminded of his undertaking to write a Foreword to Gardeners' Choice. His much-delayed MS arrives at 42 St Margaret's Street, Rochester, where Mahoney is staying, on September 3rd. It needs considerable editing. Mahoney tells him it has arrived too late for inclusion. (Bawden's text was discovered among Mahoney's papers in c.2010. It was included in facsimile in Persephone Books' 2015 reprint of Gardeners' Choice.)

*Evelyn discovers she is pregnant.

*Mahoney and his brother Jim buy a cottage in Wrotham, near Maidstone, for their mother Bessie. Mahoney, who has been living for some years in a succession of lodgings, including the Hampstead studio Evelyn rented in 1933-5, moves in too. Evelyn has not been told. Her dreams of living with Mahoney are shattered.

*Evelyn and Mahoney have separated. She works overtime preparing Gardeners' Choice for publication on her own, all in longhand. There is an unknown quantity of re-writing. It is probably this that caused Roger Folley to say, many years later, that 'Evelyn wrote most of Gardeners' Choice'. In any case it was supposed that a greater share of the writing fell to Evelyn, while Mahoney was responsible for most of the plant drawings. As time passes, however, and as more and more drawings of plants featured in Gardeners' Choice appear from the long-lost Hammer Mill Oast collection, i.e. Evelyn's residual studio, it's clear that she drew far more than the modest quantity originally assigned to her.

*In the closing months of 1937 Evelyn miscarries. It's likely that, alone of the Dunbars, her mother Florence knows.

* * *

There's a bizarre little footnote to all this. As mentioned above, Mahoney kept all Evelyn's letters to him. In 1941 he married Dorothy Bishop, primarily a calligrapher. Some years later the Mahoneys' Christmas card appeared, designed by Dorothy. Here it is, shown next to one of Evelyn's Opportunity letters from 1936.

Text ©Christopher Campbell-Howes 2022. All rights reserved.

by Christopher Campbell-Howes

is available to order online from:

%20Oast-House.jpg)

%20Smoker.jpg)

%20Rave.jpg)

%20Drinking%20Fountain.jpg)

%20Lean-To.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)