Letter to Charles Mahoney, summer 1935. Original in Tate Britain, ©Estate of Evelyn Dunbar. Unless otherwise stated, all illustrations are from the same source

Trellis? Trellis? What can Eve(lyn) mean? Certainly, there are trellises here, blown hither and thither by this mighty creature from the heavens: houses look on in astonishment, a small Mahoney-like figure raises his arms in consternation (or surrender?), chimneys are blown away, the text is littered with flying bits of trellis. Whatever is going on?

* * *

Charles Mahoney (1904-1968) lectured at the Royal College of Art from 1928 until after World War 2. His given name was Cyril, but he found himself nicknamed 'Charlie' by his RCA colleague Barnett Freedman, probably for the rhythm and euphony of 'Charlie Mahoney' and the agreeable if impertinent rhymes that might be got from it. Evelyn knew him mostly as 'Chas'.

They met in 1932, while Evelyn was pursuing a postgraduate year at the Royal College of Art. Mural painting, taught by Mahoney, was a principal element in her course. A year earlier the RCA Principal, William Rothenstein (later Sir William) urged, via the BBC, the nation's public authorities to encourage and enable mural painting in public buildings, partly to provide employment for young artists struck by the Depression. Mahoney could hardly avoid implication. The outcome was a commission to decorate the school hall at Brockley County School for Boys, now Prendergast - Hilly Fields School, in SE London. He tried to put a team of recent RCA graduates together, but only one answered the call: Evelyn Dunbar. (Later two other recent graduates signed on: Violet Martin and Mildred 'Elsi' Eldridge.)

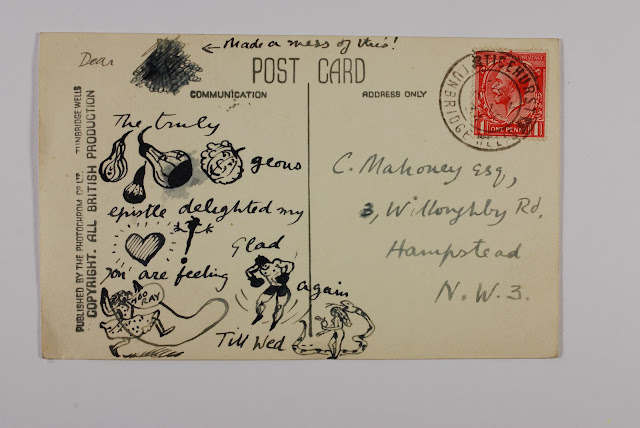

From the spring of 1933 Mahoney and Evelyn worked at Brockley, sometimes together but often apart. They fell in love, and so began a correspondence as remarkable for an emotional intensity often expressed more in drawing than in words, for its frequency (Evelyn wrote several times a week), for its almost total absence of dates, and especially for its one-sidedness: none of Mahoney's letters survives. However to start with all went merry as a marriage bell. Here is Evelyn in impish, 1934 mood:

Evelyn

enjoyed quite complex pictogram puzzles from time to time. Writing from her

aunt Clara Cowling's house in Ticehurst, East Sussex, she appears to be

saying 'The truly gorgeous [gourds + 'geous'?] epistle delighted my heart ! Glad you are feeling fighting fit

again' Then there are little cameos of a girl saying HOORAY and

skipping with delight, and finally, complete with apple and grinning snake,

Evelyn as Eve the temptress, whose figleaf appears to have fallen off.

Aha.

Like all lovers they concocted their code-words. 'Trellis' was one. Which of the two first likened the rows of Xs that trellis consists of to kisses - XXXX - no amount of latter-day playing gooseberry will reveal. So the letter above is a whirlwind, an elemental hurricane of kisses.

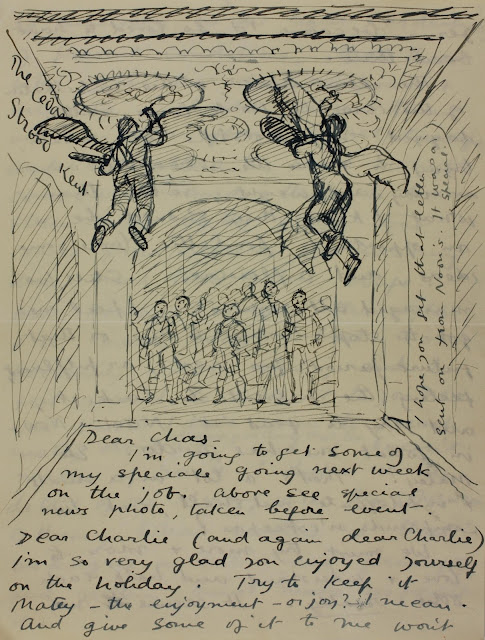

However only one kiss, and only one mini-zephyr, in this letter from the summer of 1935, in the same blue-ink and fountain-pen style as the whirlwind letter above. As usual, no date, but the address - 95 Ermine Rd, Brockley - is of the lodgings Evelyn took while working on the murals at nearby Brockley school. Or 'Broiley', as she calls it, mirroring 'Stew-dio' where Mahoney was also working in the heat of a summer's day. This shared studio was the one Evelyn rented for £13 a quarter from Noël Carrington - the Noël mentioned in the text - in Hampstead. Incidentally, 95 Ermine Road no longer exists, according to my informant Nicholas Sack, the eminent urban photographer. Where it stood there are now council flats.

More trellis on this letter, and it would be interesting to know what Mahoney had written to evoke such enthusiastic thanks from Evelyn, if only to discover what the 'boardlet' was. We can stab a guess at 'J & G': were they Joan and Geoff Rhoades, artist friends of Mahoney? And even if we're right, their cushion remains a mystery despite Evelyn's little drawing of it and the accompanying workbox. Happy days.

Dating Evelyn's letters needs a panoply of little strategies. In this hearts-and-flowers letter there's very little to go on. Ladywell is an area of Brockley, so it can be assumed she was working on the murals and writing from her lodgings at 95 Ermine Road; Jessie was Evelyn's sister, who would hardly have written to Evelyn if she had been at home in Strood. Spring flowers are in evidence, perhaps a pointer to April or May. Evelyn used blue ink fairly consistently throughout 1935. The tone is of someone happily in love. Put all this together and we arrive at a Wednesday, probably in May 1935. But does it matter all that much when it was written?

Occasionally Evelyn allowed herself - and Mahoney - the luxury of some water-colour:

* * *

Beneath this idyllic surface they were an ill-matched pair: Evelyn something of an artistic cuckoo in the nest of a Christian Scientist family of Rochester shopkeepers, comfortable without being wealthy, bourgeois and centrist in their political outlook; Mahoney, of part-Irish descent, a Londoner, one of four surviving brothers. As a child he had lost an eye in a hardly fraternal struggle for possession of a pair of scissors, which may later have affected his ability to judge depth in his paintings. He was a complex man, strongly drawn to the political left and the utopia Stalin's Russia was then thought to be, uneasy with opposition and not without some streaks of rancour.

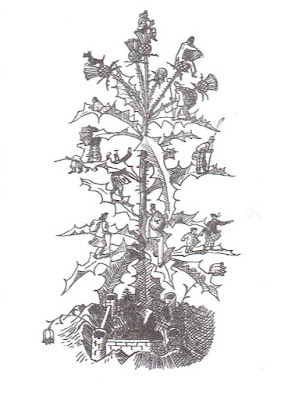

In some senses plants and gardening were the only unifying factor in their relationship. In their entourage of friends, mostly Mahoney's, and which included several of the Great Bardfield group of artists, they were nicknamed 'Adam and Eve'. Here is a typical plant letter, written from Evelyn's home address:

This is probably from 1935, when Evelyn was working on a commission from her earlier Hampstead neighbours Catherine and Donald Carswell to provide incidental drawings for a book they had edited, The Scots Week-End and Caledonian Vade Mecum for Host, Guest and Wayfarer. Does the frontispiece below owe something to Evelyn's letter, or vice versa? A unifying factor is Paul, the Dunbar's Aberdeen terrier, perched high in the branches/flowers.

Frontispiece, The Scots Week-End and Caledonian Vade Mecum for Host, Guest and Wayfarer eds. Carswell D and C, Routledge, London 1936

Behind this commission, which brought Evelyn about £1800 at today's values, lay the Carswells' neighbour and Evelyn's recent landlord, the editor and publisher Noël Carrington, a man Mahoney disliked. This put Evelyn in a quandary: throwing in her lot with Mahoney meant distancing herself from her Hampstead friends. The Brockley murals were completed by Evelyn in February 1936: Mahoney had left the project the previous May at a particularly difficult point, the painting of a ceiling. Even so, months later Evelyn sent him her notion of what it might have been like if Mahoney had contrived to stay on:

Evelyn continued to mask her disappointment, and even designed a tie for Mahoney to wear for the inauguration of the Brockley murals the following February:

Despite her disappointment over Mahoney's abandonment of the Brockley project, Evelyn saw her future linked privately and professionally with him: what joint projects could they undertake?

Through the Carswells and The Scots Week-End Evelyn now had a presence at the publishers, Routledge, via their commissioning editor, a man called Ragg. Evelyn suggested a book about gardening, a joint production between her and Mahoney. After some badgering Mahoney agreed. The writing and illustration of Gardeners' Choice kept them together, perhaps somewhat artificially, until the late summer of 1937, when they separated. Gardeners' Choice, which Evelyn hoped would stand as a metaphor for all that had been good in their relationship, appeared in good time for Christmas 1937.

* * *

The writing on the wall had been evident for some time, perhaps since Mahoney's departure from Brockley. Evelyn's letters continued, ever hopeful of a permanent arrangement, expressed through joint commissions, or a shared garden or home together, or finally through children together.

Trellis again, surrounding a flowery nook in which to spend quality time with Mahoney. 'Eves' - see the text - has to be a play on words on Evelyn's name and the evenings they spent together.

February 1936. Evelyn has taken her post, in this case a letter from Mahoney, outside beside the summer house in The Cedars garden for a bit of privacy. But who is the figure lurking behind the wall? There's no obvious answer.

The 'R's and all their social biz' refers to William Rothenstein, the RCA principal. Mahoney was at odds with the direction the RCA was beginning to take, advocating a more commercial approach to art. Not easy for Evelyn, who got on very well with Rothenstein and enjoyed his 'social biz', something she had to abandon in her support of Mahoney.

Evelyn occasionally addressed Mahoney by affectionately insulting names. 'Dearest Pig' is typical of this habit. We don't know how Mahoney responded. The figure writhing in agony, pinned to the ground by Imperturbability (as prescribed by Evelyn), is none other than Rothenstein.

Suggestions for activities to keep them together begin to feature heavily in this correspondence.

Here they are gardening together (above), and here (below) is Evelyn describing a house she has seen which might suit them both, but without actually saying as much:

By 1936 'opportunity' had become a theme-word covering the various projects which Evelyn thought she and Mahoney might envisage together. Apart from Gardeners' Choice they came to nothing. She made various attempts to personify Opportunity, some of which are examined in an earlier post, and in her final outpourings in this vein she refers to the children they might have between them -

- not that she necessarily intended to have eight children, as in the drawing above, where half of them are scrumping the fruit from Opportunity's hat. In any case Mahoney wasn't interested, and said so: children would stunt his and Evelyn's careers. In the late summer of 1937 Evelyn miscarried, Mahoney had bought a house without consulting her, and the relationship collapsed.

* * *

It says something maybe unexpected about their relationship that Mahoney kept Evelyn's letters, in their entirety and not simply the drawings, which a lesser man might have done. In due course the package, numbering some 80 letters - it's possibly that one or two might have been suppressed - passed to Mahoney's daughter, Elizabeth Bulkeley. Mrs Bulkeley nobly presented them to the Tate Archive, where they are open for anyone to inspect...

...even Evelyn's biographers: in 2016 Josephine and I spent several hours in the Tate Archive photographing this extraordinary collection, only a fraction of which is shown here. One of the saddest was written by Evelyn in blunt pencil on a much-folded piece of paper; it had evidently passed much time in Mahoney's pocket. I could just make out '...why can't you even be bothered to say hello when I pass?' I couldn't bring myself to photograph this desperately sad witness to an ill-judged relationship that had gone horribly wrong.

Text ©Christopher Campbell-Howes 2022

Further reading...

EVELYN DUNBAR : A

LIFE IN PAINTING

by Christopher Campbell-Howes

is available to order online from: